Bookshelf: How We Hold One Another

05.05.2023

About:

Each year, seniors at Maine College of Art & Design choose and define a series of independant projects that culminate to into their thesis. Required components are an artist talk about the work, an exhibition of the work, and a paper descring influences for the work.Statement:

I grew up surrounded by overflowing bookshelves. My grandmother shoving books in my hands; my dad reading me fantastical novels or toe-curling poetry; my mom shushing, peering over a new autobiography.I would always carry a book, bumping into my classmates while reading and walking up the stairs. Books were/are a one-on-one conversation between me and the author. Someone I both knew intimately and not at all.

I began writing. At first, small unconfident poems that became passing thoughts budding into blurbs morphing into stories. After years of solitary half-smiling and half-belonging, I found community with writers, readers, and book-lovers. I enveloped myself in this new comradery, realizing that I aspired to embolden those around me, amplify their voices rather than my own.

My exploration in the vessel of the book pairs with my exploration in collaboration. Books require many hands to be made and many perspectives to be conceived. From the printer to the author to the reader, expanding the definition of collaborator empowers the voices of each participant.

The Paper

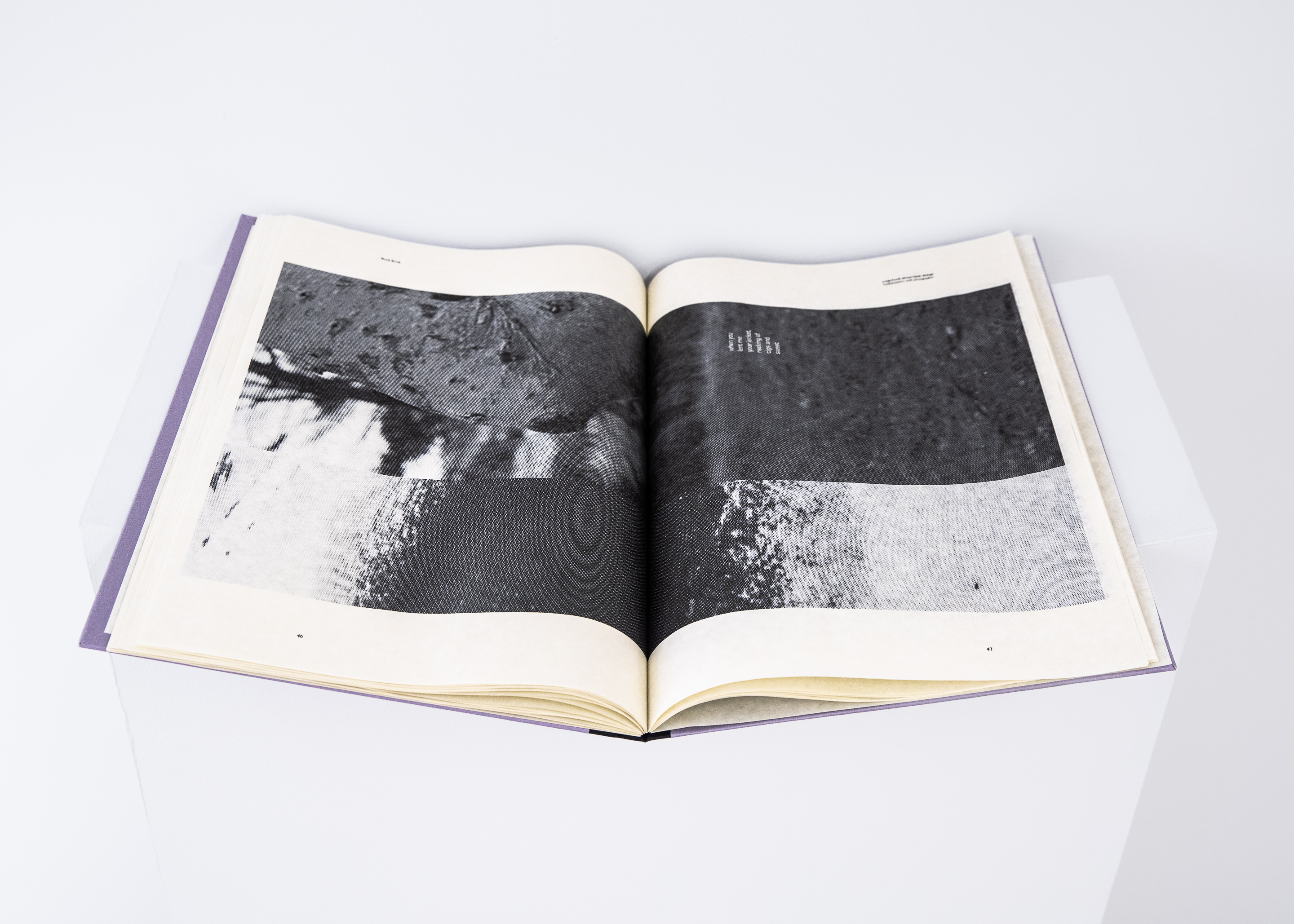

Think about a book. What does it look like?The book—the novel—is often a mass-produced rectangular object containing pages glued together, either hardcover or soft. Inside, there is mostly text, a serif script, separated by chapters, noted in a table of contents. A colophon describes the publishers, distributors, and printers. In a few decades this book will yellow, the pages will fall out, and it will be forgotten in a used bookstore.

The book—the children’s picture book—is often a mass-produced object, pages glued together, usually hardcover. There are mostly colorful pictures, with occasional text, often written in a handwritten script. If the pages are cardboard, the book will withstand a toddler’s growing teeth and tantrums. If the pages are paper, the book will become home to scribbles of crayon.

The book—the religious manuscript—is an ornate, unique object consisting of fine materials and a protective cover. Words are handwritten with calligraphic scripts. Illuminations detail scenes, and abstract ornamentations punctuate the value of this object. The high level of craft emphasizes the importance of the writings, enabling these pieces to exist over many centuries.

The book—the periodical—is a flimsy, limited edition of a collection of texts and pictures. These are the newspapers fresh off the presses, the magazines shoved into mailboxes, the zines given away. They quickly distribute new ideas, promoting relevant works from lesser known artists and writers. They are often read quickly and then forgotten in a dim coffee shop.

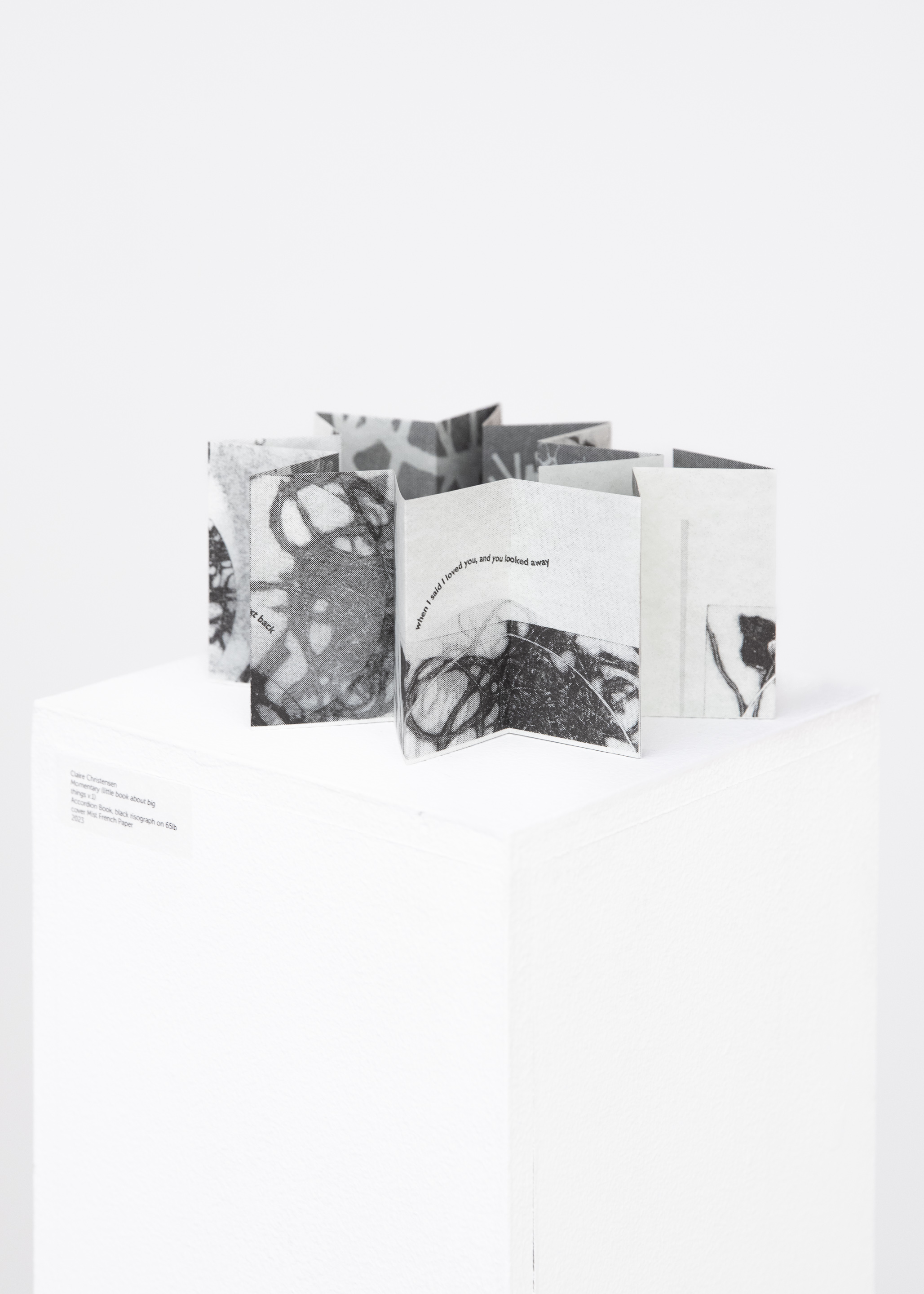

The book—the artists’ book—is a unique object, created for the sake of its object-hood. These are the experimental accordion books created from sheets of mica, the sculptural pieces constructed using tee shirts, or the thick letterpress printed visual essay. Anything can be deemed a book if the book artist declares it so. These pieces might live in a gallery or they might live in a climate controlled rare books room, always handled with gloves.

Under each definition or exploration of “the book,” the book structure acts as a vessel for text and imagery to be distributed to an audience. My working definition of “the book” is in line with Keith Smith’s notion: “If [a] person declares it a book, it is a book! If they do not, it is not.”

Read the paper

The Process Book

The Graphic Design program at the College requires that all seniors create a book describing the process of conceptualizing and realizing their thesis.See the pdf